As I’m wrapping up my work preparing inventory forms for Lee, Massachusetts’s Little Italy neighborhood, I wanted to share a bit about the research process I used for the neighborhood. The plan was to prepare a Massachusetts Historical Commission area inventory form to document the neighborhood as a whole, as the buildings are not architectural standouts but the development of the neighborhood overall is important to Lee’s history. The neighborhood was settled by Italian immigrants in the first few decades of the 20th century who arrived in Lee to work at a marble quarry directly west of the neighborhood.

For an area form, I don’t do detailed title histories of properties. Instead, I rely on sources such as census records and street directories to identify owners and residents of properties. These sources are helpful as they list residents by street address. With the census being every ten years, and street directories filling in the gaps, you can usually develop a good basic history of a house using these sources.

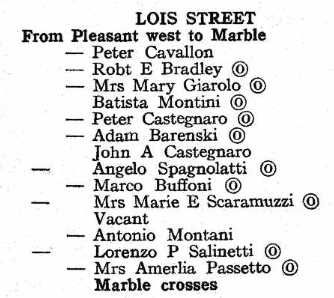

But as I began assembling sources for Little Italy, I quickly realized that my plan would not work for the neighborhood. Here you can see the 1960 street directory for one of the streets in the neighborhood. Notice something missing? Street numbers! As late as 1960, the neighborhood had not been assigned street numbers. While the lines to the left of the names indicate if a house was on the left or right side of the street, if buildings had been demolished or included multiple units, my count might be off. So while I had census records from 1910 to 1950, and street directories from the 1920s to the 1960s, none of the houses were numbered! I could not tell who was living where.

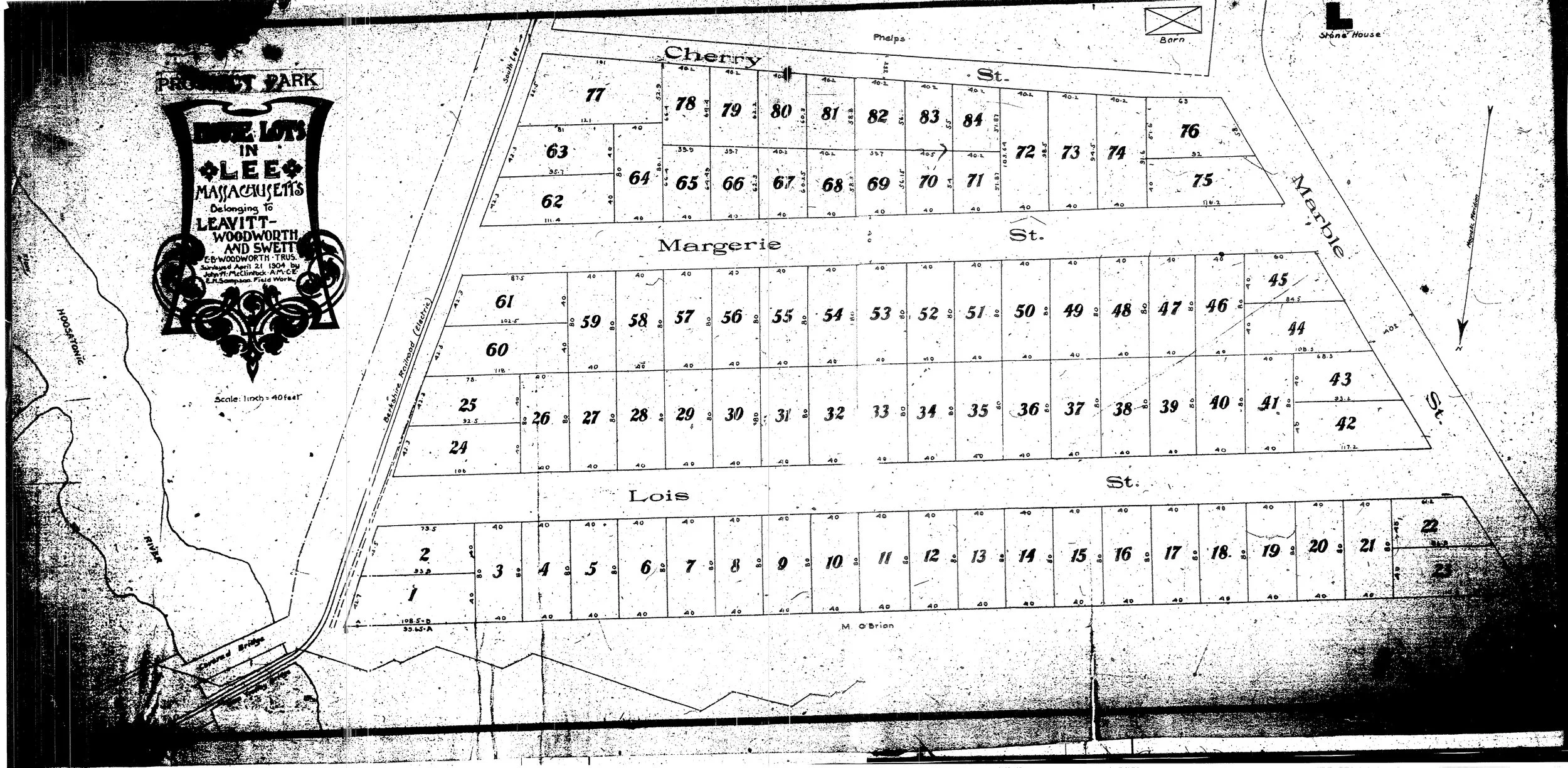

In assembling potential sources, though, I found that the Lee Library had digitized and made searchable the local newspaper, The Berkshire Gleaner - the very nosy, very detail-heavy local paper. The neighborhood was initially named Prospect Park, but by the 1910s had already acquired the Little Italy moniker. A search of those two names turned up almost 200 articles detailing the comings and goings of residents, particularly the sale of lots and the construction of houses in the neighborhood. Having also found the 1904 subdivision plan of the neighborhood via a spot-check of current deeds (current metes and bounds still reference the 1904 plan), I was able to match articles about lot sales and house construction to deed references and current properties.

In 1904, a land development group recorded a subdivision plan for the Little Italy area at the Berkshire County Registry of Deeds. Note that north is down.

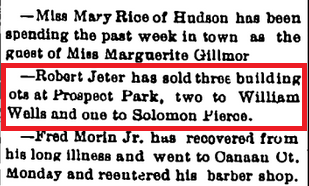

From the July 24, 1907 edition of The Berkshire Gleaner.

For example, a July, 1907 article noted Robert Jeter’s sale of three lots to two men. I was able to cross-reference Jeter and the buyers’ names in the Berkshire County Registry of Deeds grantor and grantee indexes to find the deed references for the sales. Going to the deeds, I could use the lot numbers tied to the 1904 plan given in the metes and bounds to identify the property that was transferred. In this case, the newspaper’s description of the lots as “building lots” indicated that they did not include houses, so I would know that the houses there were built after 1907. I looked for the buyers in directories and census records a year or so after that date, to see if they built and moved into a house on their lots.

This house at 50 Lois St., on lots 11 and 12 on the 1904 plan, was one of two sales mentioned in the 1907 article. The neighborhood has around twenty end houses similar to this, although with variations in fenestration, porches, and roofs.

By parsing the newspaper articles in this way, I was able to narrow down construction dates, potential first residents, and later residents for several of the buildings in the neighborhood. A slow process, but one that helped to more fully explain the development of the neighborhood, beyond using the census records to generally describe the neighborhood in ten year increments. The newspaper records, while not always available in such great detail for every community, have been hugely helpful in telling the history of Lee’s Little Italy.